“Imagine you’re baking a cake,” says Francisco Yarur Villanueva, a PhD candidate in the Department of Chemistry.

“You go to the kitchen, assemble all the ingredients — milk, sugar, eggs, flour — mix them together and bake your cake. But then you find that most of your ingredients ended up on the floor or countertop and not in the cake.”

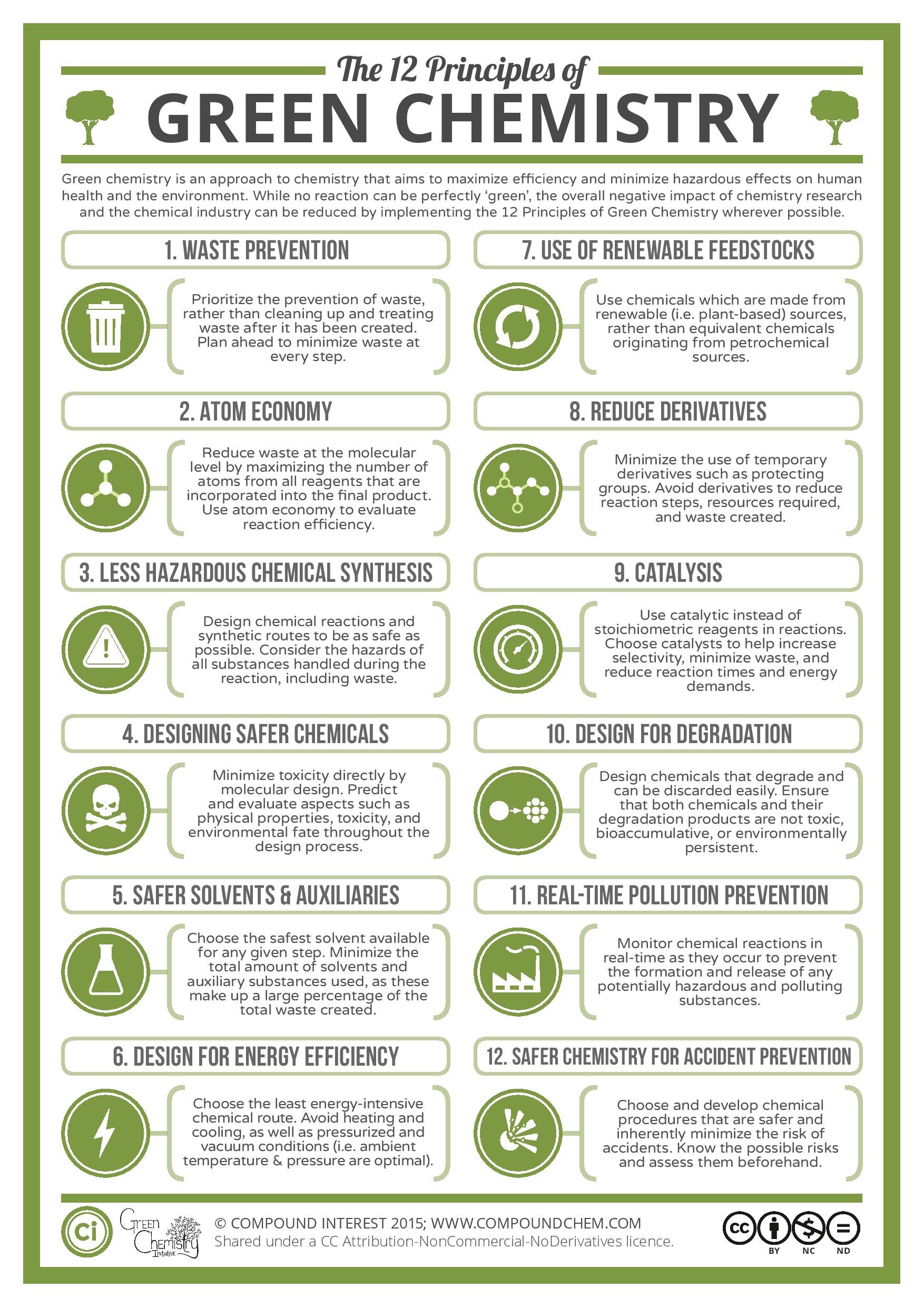

According to Yarur, this describes “atom economy,” one of the 12 principles of green chemistry designed to lessen the environmental impact of the discipline. The principle states that as much of the ingredients used to synthesize a chemical product should make it into the final product — with a minimal amount of waste or byproducts.

Other principles include using chemicals made from renewable sources, reducing energy consumption, designing safer end-products, and more.

Yarur first became interested in green chemistry as an undergraduate at Concordia University and his goal now is to incorporate its principles into his research and help make its practices more commonplace.

Yarur is a member of and symposium chair for the Green Chemistry Initiative at U of T, a student-run organization based in the Department of Chemistry aimed at promoting sustainability in chemistry research and education. He was selected to participate in the 2022 Green Chemistry Summer School organized by the American Chemistry Society (ACS). He received the Joseph Breen Memorial Fellowship from the ACS, and as a result, will be presenting his research at the Green Chemistry & Engineering Conference in June.

“I have a strong drive to tackle global environmental issues through chemistry and engineering,” says Yarur. “I believe it’s of paramount importance for chemists to focus on adapting our laboratory practices to develop greener and more sustainable procedures to decrease environmental pollution.”

A&S News spoke to Yarur about green chemistry and the ways he’s trying to incorporate its principles into his research.

Can you give an example of bad “atom economy” in chemistry?

Sure. For decades, the process for synthesizing the widely used anti-inflammatory drug ibuprofen involved six steps. It required large amounts of toxic solvents and in the end, many of the atoms used as reactants became waste. Today, however, the synthesis of ibuprofen is an often-cited example of a green chemistry success story as current processes involve only three stages, use less toxic solvents, and more of the atoms used in its synthesis end up in the final product.

How did your interest in green chemistry first arise?

My interest in green chemistry started with my interest in renewable energies — particularly solar energy conversion. As a chemistry undergrad, I did my honours research in environmental chemistry and eventually, I was one of the first students to work in a new solar energy conversion lab at Concordia doing work related to green chemistry — for example, catalysis.

This is when I learned about the 12 principles and really started to pay attention to reducing chemistry’s footprint. I knew I wanted to continue doing fundamental science, but I also decided I wanted to apply the principles while doing it. So, for example, when I joined U of T to study nanomaterials, I told myself I didn’t want to work with commonly used cadmium- and lead-based materials because of the toxicity of their constituent elements. My supervisor was supportive and flexible, and now I’m the only student in the lab not working with cadmium or lead.

Your most recent paper deals with these issues. Can you describe the research?

We were looking for visible and infrared active nanocrystals that wouldn’t contain harmful elements like cadmium, lead or arsenic. Then, I found research describing a nanocrystal material, Ag2ZnSnS4, that didn’t contain banned elements like cadmium and lead. But one of the problems is that existing methods for synthesizing it are not efficient. So, my co-authors and I worked to improve the synthesis process while optimizing Ag2ZnSnS4’s optical and electronic properties.

A green chemistry bonus to this research was the solvent employed for their purification. Common purification procedures used in the manufacture of nanocrystals use large volumes of acetone, methanol and chloroform, among other solvents. These solvents can be deemed non-green, depending on the metrics considered to evaluate greenness. In this work, we used small volumes of ethanol — a significant green improvement.

You’re a member of the Green Chemistry Initiative here at U of T and its symposium chair. Tell us about the group and the symposium.

The group has been around for over a decade, and we do a lot of outreach and education. We have a bi-weekly trivia contest in which we ask chemistry students questions that make them think about green chemistry, then we award prizes for correct answers. We organize one seminar per month in which we invite an expert to speak about green-chemistry research. We have waste awareness and women in green chemistry campaigns. And, we have a YouTube channel where you’ll find our videos, including a video about each of the 12 green-chemistry principles.

Plus, we hold an annual symposium which is attended mostly by masters and PhD students from across Canada and some from the U.S. This year’s is the eighth, with speakers from academia and the private sector, and a panel discussion titled Bridging the Gap between Industry and Academia.

You must still meet people who are resistant to making chemistry greener and think the status quo is fine. What do you say to them?

There are many who would say: If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. But in terms of sustainability and the environment, I would say that chemistry processes are broken. We’re using toxic materials and unsustainable practices — so, we need to fix it.

I think more and more undergraduate students feel closer to the environmental crisis and understand how critical the situation is. So, I point them and others to educational resources from organizations like Beyond Benign and the ACS GCI. And I tell them: Don’t be afraid to learn more about green chemistry and don’t be afraid to challenge the status quo. Don’t be afraid to throw yourself into this — just jump in with both feet!